Canadian Members of Parliament are set to vote on Bill C-14, also known as the Medical Assistance in Dying Bill. The bill will repeal numerous legal protections against assisted suicide and euthanasia in the Criminal Code, in line with 2012 Supreme Court of Britisch Columbia and 2015 Supreme Court of Canada decisions that found such protections unconstitutional. Notably, both Parliament and the courts have reversed course on previous decisions that upheld the constitutionality of those same legal protections under nearly identical circumstances.

Bill C-14 has been promoted by the federal government as taking a conservative approach, only allowing assistance in cases where “death is reasonably foreseeable” and implementing “safeguards” against abuse. However, as written it clearly contemplates broadly legalising assisted suicide and euthanasia, even for “mature minors” and those with mental illness.

Conspicuously absent from the debate has been any discussion about the experience with similar legislation in the United States and European Union, where both legal and medical reviews have been decidedly critical, second-guessing the wisdom of even having such legislation. That’s likely because the rationale for such laws, the topic to be covered here, is questionable at best.

First, kill all the lawyers

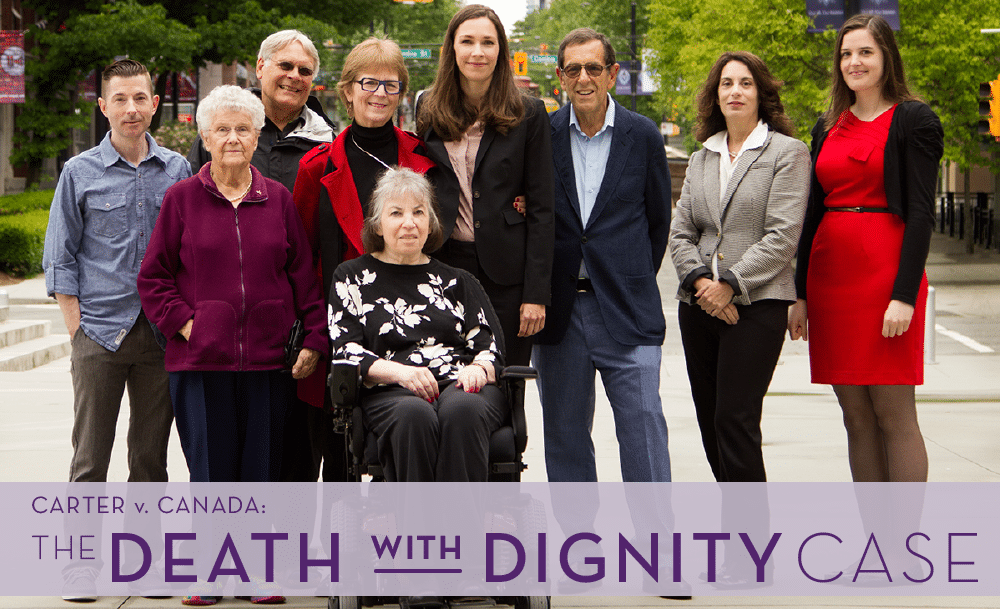

Before getting into the research, it’s worth briefly reviewing the public relations material presented by the lawyers who brought forward the constitutional challenge to legalise assisted suicide and euthanasia in Canada.

The British Columbia Civil Liberties Association presents brief profiles of several individuals on whose behalf it filed its legal challenges.

Gloria Taylor

The first presented is Gloria Taylor, who was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis at age 61. Her doctor supposedly said that “the disease would likely paralyze her within six months, and would kill her within a year”. BCCLA paints a picture of a brave fighter who outlived a grim prognosis, living an additional three years.

Which actually presents the first issue with assisted suicide and euthanasia: Misdiagnosis. According to the ALS Association, the average life expectancy after diagnosis is 3 to 5 years. 10 percent go on to live more than 10 years post-diagnosis. Some, like renowned astrophysicist Stephen Hawking, go on to live long, productive lives well beyond that.

Misdiagnosis can lead to different proposed courses of treatment. A patient given one year to live would likely be relegated to palliative care, whereas one with a stronger prognosis could be counselled on available medical and lifestyle interventions. (A bit off-topic, but there has been research linking lifestyle factors to ALS development and progression.)

When assisted suicide is on the table, a misdiagnosis could effectively lead to premature death.

We’re told Gloria raised a glass and said a toast to celebrate her ‘victory’, becoming the first Canadian granted the right to assisted suicide by the SCBC. Gloria’s quality of life was not so compromised. She was conscious, coherent and capable of enjoying life’s moments.

And, as it turned out, Gloria didn’t need a physician’s assistance after all. She died of natural causes, although the BCCLA spins it as “suddenly and unexpectedly”, contradicting its assertion she had far outlived a grim prognosis.

That popular saying about how there are only two certainties in life, death and taxes, is half true. While the wealthy can effectively avoid the latter, none have ever avoided the former. As such, no one has ever actually needed ‘assistance in dying’. Let’s be honest and call it what it is: physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia.

Kay Carter

The face of the BCCLA’s SCC case, it’s worth noting that Kay Carter would not have qualified for physician-assisted suicide under Bill C-14. Her death was not “reasonably foreseeable”.

Rather, her case presented the slippery slope, where assisted suicide is requested simply due to a perceived decline in quality of life.

Her profile notes she suffered from a degenerative condition, was “fiercely independent” and simply wished to “leave life on her own terms”.

The nature of degenerative diseases is that they are progressive. While BCCLA paints a picture of a woman “confined to a wheelchair, unable to feed herself or go to the bathroom without assistance and chronic pain”, she got to such a state after years of decline. If she truly was fiercely independent and wished to leave life on her own terms, she could have committed suicide on her own at any point leading up to the state which the profile depicts, and even in said state.

While assistance in committing suicide was illegal until recently, suicide itself has been legal in Canada since 1972. As an unfortunate spate of recent US celebrity premature deaths has served to illustrate, taking one’s own life is not only easy and painless, it’s so much so that many individuals end up taking their own lives by mistake.

Elayne Sharpay

The choice of words in Elayne Sharpay’s profile, along with her quote, are interesting. Like Kay Carter, she also suffers from a degenerative disease, multiple sclerosis. She wishes to avail herself of physician-assisted suicide because she doesn’t want to wait until she is “trapped in her own body”.

That turn of phrase is troubling, as it’s often used by those advocating transgender surgery for people with gender identity issues, and more generally by depressed, suicidal young people. That’s worth underscoring in light of the fact Bill C-14 contemplates expanding access to assisted suicide and euthanasia to “mature minors” and those with mental illness.

BCCLA quotes her as saying, “As the law now stands, I… will have to act alone, while I still can. My only choice for bringing about my death unassisted are self-starvation, over-medication, or some violent self-inflicted injury.”

As just noted, ending one’s own life is neither illegal nor difficult. If people who were in otherwise fair health could accidentally end their lives with a combination of readily available anti-anxiety medications and sleeping pills, those who are in poor health intending to end their own lives certainly can do so with little effort or suffering.

Also, with regard to “over-medication”, exactly what would physician assistance in suicide or euthanasia entail other than either prescribing or administering a lethal dose of medication(s)?

Rationalising the otherwise irrational

The insistence on having a physician do it is really about squeamishness and the over-used-but-ill-conceived “death with dignity” argument. Being found dead in an elevator, or slumped over in a chair or bathtub seems icky. Having a doctor facilitate suicide in a controlled manner / environment seems less icky.

Besides, the reason most people are reluctant to kill themselves is that at some level they find suicide ethically and morally objectionable. Whether it’s instinct (nature), social conditioning (nurture), or a combination thereof, most rational, sound-minded individuals simply could not bring themselves to take their own lives. Having someone else do it, especially one state-sanctioned to, at some level moderates the otherwise ethically objectionable and rationalises the otherwise seemingly irrational idea of ending one’s own life.

Dignity is not determined by how a life ends, but how it was lived up until its inevitable conclusion. ‘Death with dignity’ is just a nice turn of phrase to make those who’d chose to end their lives as a matter of convenience feel less conflicted about their choice.

First do no harm

A point not directly addressed in either the 2015 SCC decision or Bill C-14 is the conflict presented by physicians’ obligation to provide care for and not contribute to the demise of patients health. In addition to their own personal morals and ethics, the Canadian Medical Association Code of Ethics, in line with international standards, still obliges a doctor to “Provide for appropriate care for your patient, even when cure is no longer possible, including physical comfort and spiritual and psycho-social support.” Even the most liberal interpretation of “care” precludes facilitating a patient’s death.

But what if the Code is changed, and say a doctor who doesn’t have much regard for the value of life decides to open assisted suicide clinics? Again, neither the 2015 SCC decision nor Bill C-14 contemplate such an outcome. While the proposed legislation preamble notes “vulnerable persons must be protected from being induced… to end their lives”, it proposes no practical means of ensuring such protection – likely because there isn’t any practical means of doing so. That’s actually the main reason why assisted suicide and euthanasia had been illegal up until now.

Aside: A hallmark of any law that’s bound for abuse is excessive reliance on ‘reasonableness’. Bill C-14 hinges on “reasonable” foresight, mistaken belief, knowledge, care and skill.

Curious timing

As already mentioned, both Parliament and the courts have done an about-face on assisted suicide and euthanasia. In the early and mid-1990’s numerous private members’ bills seeking to amend the Criminal Code to legalise assisted suicide and euthanasia were either defeated or dropped. Concurrently, the BCSC and SCC both found protections against assisted suicide and euthanasia in the Criminal Code did not violate an individual’s rights. Like Gloria Taylor and Kay Carter, Sue Rodriguez, the applicant/appellant in those cases, also lived in B.C. and had ALS.

So what’s changed?

It’s been argued that Canadian values have changed, but there’s little evidence of this. The only recent (2014) poll that’s been made public was conducted on behalf of partisan group Dying with Dignity, with the obligatory skewed questionnaire wording; it was also conducted online, rendering it all but meaningless (self-selection bias). Besides, values do not fundamentally change in less than twenty years.

What has changed is the demographic elephant in the room: The first wave of baby boomers started turning 65 the same year the SCBC reversed course to find legal protections against assisted suicide and euthanasia unconstitutional.

While the image of fit and active retired seniors is commonly portrayed in popular media, the stats tell a different story. As the title of one 2008 research paper available on PubMed succinctly put it, there’s the Financial Burden of Overweight and Obesity among Elderly Americans: The Dynamics of Weight, Longevity, and Health Care Cost.

Despite comprising a relatively modest share of the total population, those over 65 have accounted for the majority of medical care expenditure in recent years. Poor lifestyle choices earlier in life lead to “chronic diseases, the development of functional disabilities” and “acute comorbidities” in old age. Governments will struggle with public medical care expenditures as baby boomers age 65 and over comprise a significant share of the population over the coming decade.

Opponents of assisted suicide who caution about potential compromises in care for the elderly have reason to be concerned. To what extent cuts and compromises in care encourage those suffering to consider ending their own lives is a question that should never occur in a civilized society, but yet invariably has to be considered once physician assisted suicide and euthanasia are on the table.

Also, let’s be frank: Lawyers make a killing (bad pun intended) off the elderly. Advance directives will generate additional billable hours in end-of-life and estate planning consultations, while the vagueness and potential abuse of any such law and supposed safeguards will inevitably see lawsuits sprouting up across the country for years to come.

To borrow a term popular with lawyers, assisted suicide and euthanasia appear to be less about compassion and ‘death with dignity’ than about some rather unfortunate pecuniary interests.